The Killing Contest That Made Headlines: From 1937 Newspaper to Historical Fiction

- mitchirion

- Jul 11, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

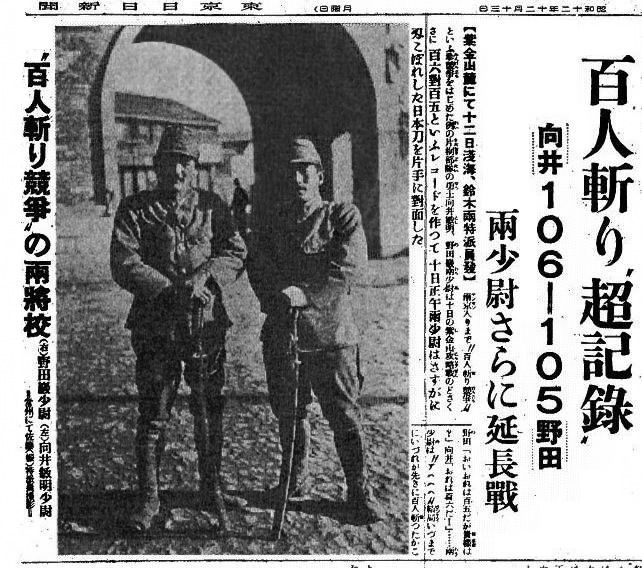

On December 13, 1937, as Japanese forces captured Nanking, the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun published what its editors considered a thrilling war story. The article, written by reporters Kazuo Asaumi and Jiro Suzuki, detailed a "contest" between two Japanese officers—Second Lieutenant Toshiaki Mukai and Second Lieutenant Tsuyoshi Noda—to see who could first kill 100 Chinese people with their swords. The photograph accompanying the story, taken by Shinju Sato in Changzhou on December 12, 1937, showed the two officers smiling beside their blood-stained blades.

To the Japanese public, this was presented as evidence of their soldiers' martial prowess and fighting spirit. To history, it stands as documentation of systematic dehumanization—a glimpse into how ordinary men became participants in genocide.

The Banality of Documented Evil

What makes this newspaper account particularly chilling is its casual tone. The reporters wrote about mass murder as if covering a sporting event, complete with running tallies and competitive banter. When both officers exceeded 100 kills, the newspaper playfully suggested they extend the contest to 150. The photograph shows Mukai and Noda as clean-cut young men, indistinguishable from countless other soldiers—a reminder that atrocity often wears an ordinary face.

This documentation serves a crucial historical purpose. Unlike many wartime atrocities that were hidden or denied, the "killing contest" was proudly publicized, providing irrefutable evidence of the systematic nature of the violence that engulfed Nanking. The officers themselves were later tried and executed for war crimes, with this very newspaper article serving as evidence of their guilt.

Fiction's Role in Bearing Witness

In Nanking Safety Zone, this historical reality manifests through the character of Lieutenant Noda Takeshi, whose scarred face and brutal nature embody the transformation of young soldiers into instruments of terror. The novel's beheading scene—difficult as it is to read—serves not to sensationalize violence but to force readers to confront the human cost of what newspaper accounts reduced to mere statistics.

Historical fiction carries unique responsibilities when dealing with such material. Unlike academic histories that necessarily maintain scholarly distance, novels can bridge the gap between historical fact and human understanding. They can help readers grasp not just what happened, but how it felt to live through such events—both for victims and witnesses.

The Importance of Uncomfortable Truths

The "Contest to Cut Down 100 People" challenges us to grapple with uncomfortable questions: How do ordinary individuals become capable of such acts? What social and psychological mechanisms enable systematic dehumanization? How do we bear witness to atrocity without becoming overwhelmed by its horror?

In Nanking Safety Zone, these questions play out through characters like George Fitch, who must document atrocities while maintaining the emotional stability necessary to save lives. The novel's most difficult scenes echo real testimonies from the International Safety Zone archives—accounts that are painful to read but essential to preserve.

Literature as Memorial

When we read about Lieutenant Noda's actions in Nanking Safety Zone, we're not just engaging with fiction—we're participating in the act of remembrance that victims and survivors demanded. Witnesses like George Fitch risked their lives to document and smuggle out evidence specifically so the world would not forget.

The novel's unflinching portrayal of violence serves the same purpose as that newspaper photograph from 1937, though with opposite intent. While the Japanese reporters sought to celebrate brutality, historical fiction can help us understand its human cost and moral implications.

The Responsibility of Memory

Eighty-six years after that newspaper article appeared, the "Contest to Cut Down 100 People" remains a sobering reminder of humanity's capacity for evil. But it also demonstrates the power of documentation—how evidence preserved by witnesses, journalists, and writers can outlast the regimes that created it.

Nanking Safety Zone joins a crucial conversation about how we remember atrocity, how we honor victims, and how we educate future generations about the consequences of hatred. In bringing characters like Lieutenant Noda to life, the novel doesn't ask us to understand or forgive—it asks us to witness, to remember, and to recognize the human capacity for both evil and extraordinary courage.

The most important stories are often the most difficult to tell. But as George Fitch understood when he smuggled film evidence out of Nanking, some truths are too important to remain silent about—no matter how uncomfortable they make us.

Comments